We want to produce wildly better teaching and learning experiences in schools. And in many ways, the moment feels right.

Technology, especially generative artificial intelligence, offers real promise. It can reduce time spent on administrative tasks, surface learning patterns across classrooms, support differentiated instruction and create new opportunities for personalization.

But we’ve been here before.

From filmstrips to flipped classrooms, the arc of educational technology often tends to reinforce the usual ways of doing school. Too often, new tools are deployed to make existing structures more efficient and to not challenge the assumptions behind them.

This pattern is especially evident when we consider how we organize educators. Most tools have only been utilized to enhance the existing model of school staffing, optimizing the familiar instead of enabling the transformative.

CCTV. Interactive whiteboards. Tablets. Learning management systems. Each arrived with fanfare, and each brought real benefits. But in nearly every case, the tool was dropped into an outdated system and shaped by it. These tools each offered value, but because they were implemented inside an unchanged school structure, their impact was not fully realized.

While tools like AI hold great promise, their effectiveness depends on both the structures of schooling — how we organize time, roles and relationships — and the systems that undergird those structures: the policies, assumptions and routines that determine what school looks like.

A powerful tool in a constrained system

At its best, AI can make instruction more adaptive, feedback more immediate and planning more efficient. But these benefits are severely limited when confined to the dominant model of schooling: one teacher, one classroom, one group of students.

This staffing model places enormous demands on individual educators. It limits flexibility, and it assumes a level of uniformity among students that doesn’t reflect reality.

Inserting AI into that structure may reduce friction, but it won’t unlock transformation. We’ll get better worksheets, faster grading, soother lesson sequencing. But, generally, we won’t get fundamentally different learning experiences.

In a structure this rigid, even the smartest tools underdeliver.

We’ve seen this before

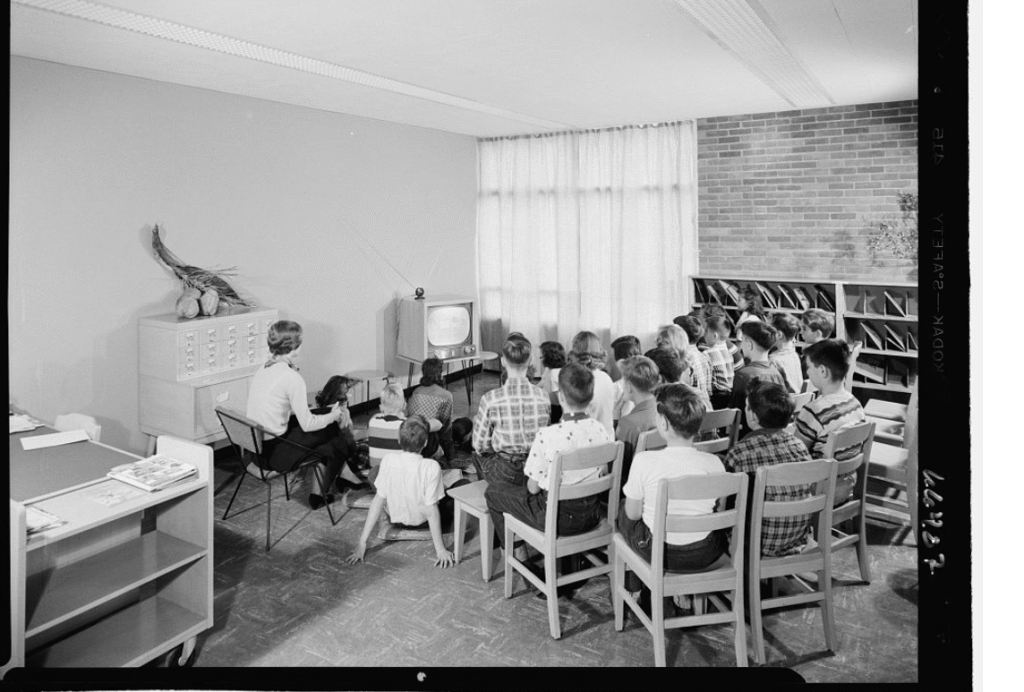

In the 1950s and ’60s, a wave of technological optimism swept into schools. Film projectors, television broadcasts, “programmed instruction” machines, videotape and closed-circuit television were heralded as breakthroughs that could modernize education. These tools came with promises of efficiency, personalization and access to higher-quality instruction. But in most cases, they were deployed within the traditional one-teacher, one-classroom model. Their use optimized existing routines rather than transforming them.

Television lessons became stand-ins for live instruction. Filmstrips and teaching machines drilled students on isolated facts. Rarely did these tools provoke shifts in how time was structured, how educators collaborated or how students engaged in learning.

There were exceptions.

In Wausau, Wisconsin, a team-based staffing model explicitly designed for integration with audiovisual tools flipped the script. In this model, a lead teacher presented content to a large group of students using team members’ expertise and a suite of tools, including films, filmstrips, overhead projectors, CCTV and guest experts. Following the large-group presentation, students rotated through small-group lab sessions and discussion sections led by other team members. The technology, in the context of a team-based staffing model, created conditions for co-planning, collaboration and flexible use of time and space.

The difference wasn’t just the tools. It was the structure surrounding them. Wausau’s instructional design intentionally redistributed teaching responsibilities, reorganized student time and embedded media in a way that complemented team-based staffing.

But this model was somewhat rare. In most schools, scheduling, staffing and curriculum delivery remained tethered to traditional norms. Over time, the exceptional cases were the ones that disappeared. What endured was the model where technology reinforced the status quo.

The takeaway is not that those technologies failed. It’s that without changes to the underlying structures — schedules, roles, grouping — tools are likely to bend toward existing paradigms of teaching and learning. Even the most promising innovations can be neutralized by the gravity of the dominant system.

If you want to unlock AI, start with staffing

Here’s the good news: we can do something different with AI.

We can choose to challenge the assumptions baked into today’s schooling model. We can ask different questions, not just “What can this tool do?” but “In what kind of system is this tool being asked to work?”

And most importantly, we can redesign that system.

If we want to unleash the full power of AI in schools, we need to rethink how adults are organized around students. That means moving away from one-teacher-per-classroom structures and toward educator teams: groups of teachers who share students, coordinate instruction and bring different areas of expertise to the table.

Team-based models do more than ease workloads. They create the conditions for dynamic grouping, shared instructional decision-making and real-time responsiveness to student needs. These are exactly the capacities AI is well-positioned to augment.

A new paradigm with AI and team-based staffing

When educators work in team-based staffing models, AI becomes something more than an individual assistant.

AI can:

- Analyze data across shared rosters to identify needs and trends

- Generate differentiated materials aligned to a team’s interdisciplinary goals

- Help coordinate schedules, communication and planning across educators

- Automate low-value tasks so that teams can focus on high-value collaboration and relationship building

But none of that is possible if the system still expects one teacher to do everything, in isolation, for a static group of students.

The structure — how we group students, assign educators and organize time — matters more than any single tool.

Co-design the tool and the system

The biggest mistake we can make now is assuming that AI will deliver transformation on its own. AI is a powerful enabler, but its impact will be lessened in a model that was built for teaching in a different era. If we want it to deliver on its promise, we need to update the paradigm it’s being asked to operate within.

And that starts with questioning the deepest assumptions about how schools are staffed, how time is structured and how responsibility for students is shared.

The future isn’t just smarter tools, it’s smarter systems.

We don’t need to wait for the perfect version of AI. And we don’t need to delay adoption until every school is restructured.

But we do need to be clear-eyed about what it takes to make AI more than just a tool to boost productivity.

That means building systems where teams of educators, supported by well-designed tools, can collaborate, adapt and focus on what really matters: meeting the needs of every student.

Let’s not ask technology to do what only a system can. Let’s build the system that makes the most of the technology we have. Because the future of AI in education won’t be determined by the tools we adopt. It will be shaped by the systems we’re brave enough to redesign.